In part one, I mentioned a ‘nagging suspicion’:

aren’t (1) the fantastically optimistic projections around objective data & AI, and (2) the increasingly high-profile crises of fake news, algorithmic bias, and in short, ‘bad’ machinic information, linked in some way? And aren’t both these hopes and fears rooted, perhaps, in the Enlightenment’s image of the knowing subject?

As usual, we’re caught up in two seemingly opposite fantasies. First, that the human is a biased, stupid, unreliable processor of information, and must be augmented – e.g. by the expanding industry of smart machines for self-tracking. Second, that the individual can know for themselves, they can find the truth, if only they can be more educated, ingest more information – e.g. by watching more Jordan Peterson videos.

Below are some of my still-early thoughts around what we might call the rise of personal truthmaking: an individualistic approach that says technology is going to empower people to know better than the experts, often in cynical and aggressive opposition to institutional truth, but a style that we find in normative discourses around fact-checking and media literacy as well as by redpilled conspiracy theorists, and in mainstream marketisation of smart devices as well as the public concern around the corruption of politics.

Smart machines

Let’s start with the relatively celebrated, mainstream instance, a frontrunner in all the latest fads in data futurism. Big data is passé; the contrarian cool is with small data, the n=1, where you measure your exercise, quantify your sleep, analyse your productivity, take pictures of your shit, get an app to listen to you having sex, to discover the unique truths about you and nobody else, and use that data to ping, nudge, gamify yourself to a better place.

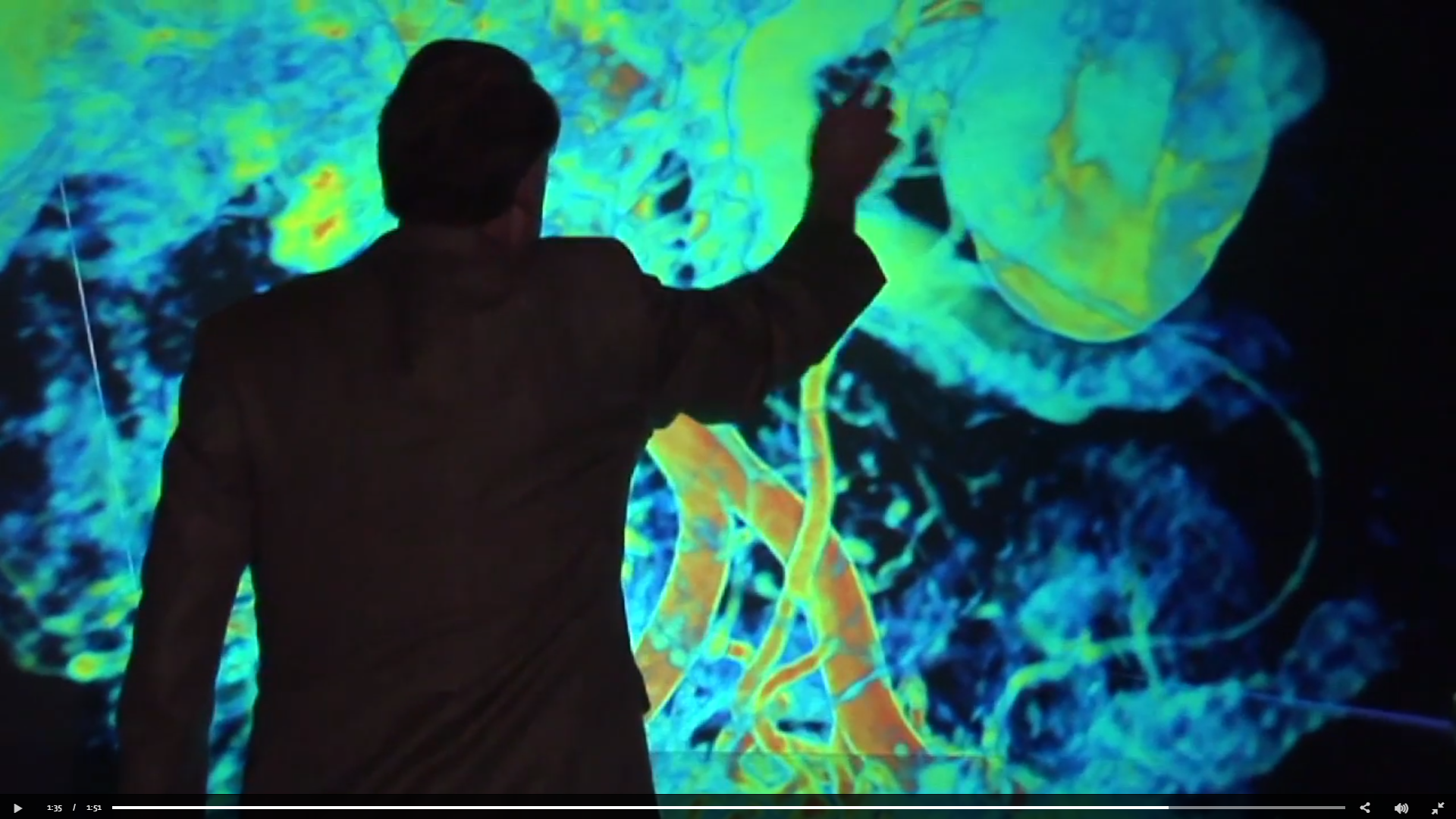

Implicit here is a clear message of individual empowerment: you can know yourself in a way that the experts cannot. Take the case of Larry Smarr, whose self-tracking exploits were widely covered by mainstream media as well as self-tracking communities. Smarr made a 3D model of his gut microbiota, and tracked it in minute detail:

This, Smarr says, helped him diagnose the onset of Crohn’s disease before the doctors could. He speaks about the limitations of the doctor-patient relationship, and how, given the limited personal attention the healthcare system can afford for your own idiosyncratic body and lifestyle, you are the one that has to take more control. Ironically, there is a moment where Kant, in his 1784 What is Enlightenment?, broaches the same theme:

It is so easy to be immature [unmündigkeit]. If I have […] a doctor who judges my diet for me […] surely I do not need to trouble myself. I have no need to think, if only I can pay.

To be sure, Kant is no proto-anti-vaxxer. Leaving aside for a moment (though a major topic for my research) the many readings of aufklärung and its place in historicising the Enlightenment, we can glimpse in that text a deep tension between the exhortation to overcome tutelage, to have the courage to use your own understanding, and the pursuit of universally objective truth as the basis for rationalisation and reform. And it is this tension that again animates the contemporary fantasy of ubiquitous smart machines that will know you better than you know yourself, and in the process empower a knowing, rational, happy individual.

Now, it just so happens that Larry Smarr is a director at Calit2, a pioneer of supercomputing tech. He has the money, the tech savvy, the giant room to install his gut in triple-XL. But for everybody else, the promise of personal knowledge often involves a new set of dependencies. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, the selling point of many of these devices is that they will collect the kind of data that lies beyond our own sensory capabilities, such as sleep disturbances or galvanic skin response, and that they will deliver data that is objective and impartial. It’s a kind of ‘personal’ empowerment that works by empowering a new class of personalised machines to, the advertising mantra goes, ‘know us better than we know ourselves’.

The book will focus on how this particular kind of truthmaking begins with the image of the hacker-enthusiast, tracking oneself by oneself using self-made tools, and over time, scales up to the appropriation of these data production lines by insurance companies, law enforcement, and other institutions of capture and control. But here, we might ask: how does this particular dynamic resonate with other contexts of personal truthmaking?

Redpilling

We might recall that what’s happening with self-tracking follows a well-worn pattern in technologies of datafication. With the likes of Google and Amazon, ‘personalisation’ meant two things at the same time. We were offered the boon of personal choice and convenience, but what we also got was a personalised form of surveillance, manipulation, and social sorting. In the world of data, there’s always a fine print to the promise of the personal – and often it’s the kind of fine print that lies beyond the reach of ordinary human lives and/or the human senses.

Fast forward a few years, and personalisation is again being raised as a pernicious, antidemocratic force. This time, it’s fake news, and the idea that we’re all falling into our own filter bubbles and rabbit holes, a world of delusions curated by youtube algorithms. When Russian-manufactured Facebook content looks like this:

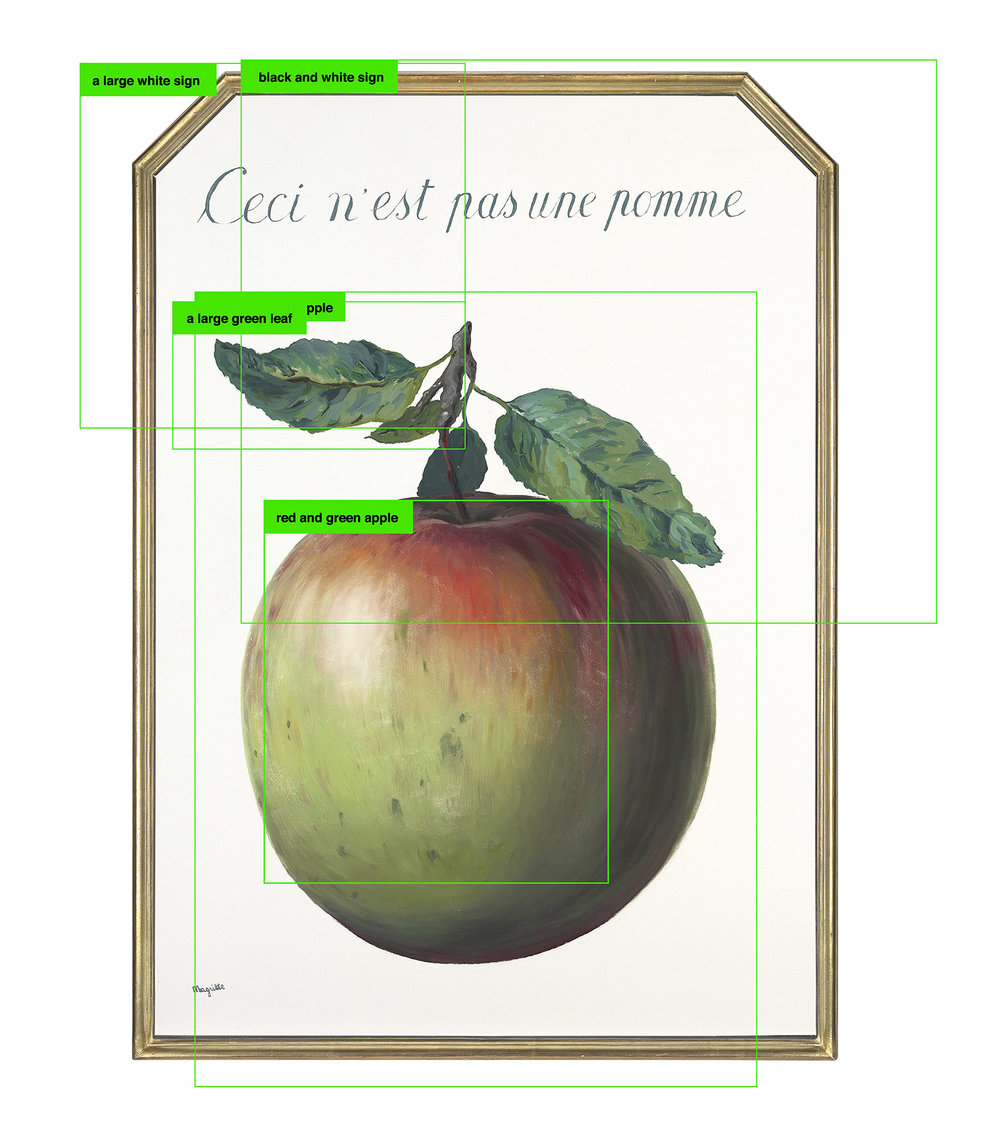

we find no consistent and directly political message per se, but a more flexible and scattershot method. The aim is not to defeat a rival message in the game of public opinion and truthtelling, but to add noise to the game until it breaks down under the weight of unverifiable nonsense. It is this general erosion of established rules that allows half-baked, factually incorrect and otherwise suspect information to compete with more official ones.

We recognise here the long, generational decline across many Western nations of public trust in institutions that folks like Ethan Zuckerman has emphasised as the backdrop for the fake news epidemic. At the same time, as Fred Turner explains, the current disinformation epidemic is also an unintended consequence of what we thought was the best part about Internet technologies: the ability to give everyone a voice, to break down artificial gatekeepers, and allow more information to reach more people.

Consider the well known story of how the 2015 Charleston shooter began that path with a simple online search of ‘black on white crime’ – and stumbling on a range of sources, showing him an increasingly funneled branch of information around crime and race relations. In a way, he was doing exactly what we asked of the Internet and its users: consult multiple sources of information. Discover unlikely connections. Make up your own mind.

The same goes for the man who shot up a pizza restaurant because his research led him to believe Pizzagate was real. In a handwritten letter, Welch shows earnest regret about the harm he has done – because he sought to ‘help people’ and ‘end corruption that he truly felt was harming innocent lives.’

Here we find what danah boyd calls the backfire of media literacy. It’s not that these people ran away from information. The problem was that they dove into it with the confidence that they could read enough, process it properly, and come to the secret truth. Thus the meme is that you need to ‘redpilling’ yourself, to see the world in an objective way, to defeat the lies of the mainstream media.

Once again, there is a certain displacement, the fine print, parallel to what we saw with self-tracking. Smart machines promise autonomous self-knowledge, but only by putting your trust in a new set of technological mediators to know you better than you know yourself. Redpilling invites individuals to do their research and figure out their own truth – but you’ll do it through a new class of mediators that help plug you into a network of alternative facts.

Charisma entrepreneurs

The Pizzagate shooter, we know, was an avid subscriber to Alex Jones’ Infowars. The trail of dependencies behind the promise of individual empowerment reveals shifting cultural norms around what a trustworthy, authentic, likeable source of information feels like.

America, of course, woke up to this shift in November 2016. And in the days after, the outgoing President offered a stern warning about the complicity of our new media technologies:

An explanation of climate change from a Nobel Prize-winning physicist looks exactly the same on your Facebook page as the denial of climate change by somebody on the Koch brothers’ payroll.

The assumption being, of course, that we would universally still find the Nobel a marker of unquestionable trust, and vice versa for Koch money. But what if a Harvard professorship is no longer such an unquestioned seal of guarantee, and what if being funded by oil money isn’t a death knell for your own credibility about climate change?

To describe these changes in terms of cynicism and paranoia is to capture an important part of this picture, but not all of it. We rarely pass from a world of belief to a world without, but from one set of heuristics and fantasies to another. What recent reports such as one on the ‘alternative influence network‘ of youtube microcelebrities reveals is the emergence of a certain charismatic form of truth-peddling.

By charismatic, I am contrasting the more serious, institutionalised bureaucratic styles to what Weber had called ‘charismatic authority’ [charismatische Herrschaft]: that which attracts belief precisely through its appearance as an unorganised, extraordinary form of truth. It’s critical here to distinguish this charisma from some internal psychological power, as if certain people possess a magical quality to entrance others. Weber considered charisma in more or less relational terms, as an effect of others’ invested belief, and something which often undergirds more institutionalised forms of power as well. The key is to understand charisma’s self-presentation as an explicitly extra-institutional circuit, through which actors are able to promise truth and action too radical for normal process, and to claim a certain ideological purity or proximity to Truth beyond the messiness of the status quo.

We can immediately recognise how alternative influencers, elements of the far-right, etc. have sought to turn issues like anti-political correctness into a marker of such charismatic authority. And individuals like Jones become exhibits in the emerging performative styles of such charisma, from his regular Mongol horde-like forays into the mainstream to pick up notoriety, or his self-righteous masculine rage as a default emotional state:

But we should add to that a couple of slightly less obvious dimensions, ones which make clear the parallels and resonances across the different businesses that sell the fantasy of personal truthmaking.

The first is that influencers like Jones consistently claim that they are the rational ones, they are the ones that go for scientific evidence, they are the true heirs of the Enlightenment. The common refrain is: I’m not gonna tell you what to think: I just want to inform you about what’s happening, about Pizzagate, about fluoride in your water, about the vaccines, and let you make up your own mind. The reams of paper strewn about Jones’ desk, regularly waved at the camera with gusto, are markers of this seeming commitment to Reason and data – even though, in many cases, this ‘evidence’ is simply Infowars articles reprinted to testify on Infowars the show.

Alex Jones doesn’t reject the Enlightenment; he wants to own it.

Second, all this is further complicated by the commercialised structure of this charismatic truthmaking. Alex Jones isn’t just a fearless truthspeaker, but also a full time vitamin peddler. While Jones works to obscure his exact revenue and audience numbers, his ‘side’ business of dubious supplements has grown into a major source of funding that helps support the continued production of political content. In his many infomercials seeded into the show, Jones touts products like Super Male Vitality – a mostly pointless mixture of common herbal ingredients packed with a premium price and a phallic rubber stopper.

Recently, Jones has updated his stock with products like “Happease” – “Declare war on stress and fatigue with mother nature’s ultimate weapons” – in a clear nod to the more dominant market of highly feminised wellness markets (think Gwyneth Paltrow’s goop and its ‘Psychic Vampire Repellent’). The connection between fake news and fake pills is made clear in one of Jones’ own sales pitches:

You know, many revolutionaries rob banks, and kidnap people for funds. We promote in the free market the products we use that are about preparedness. That’s how we fund this revolution for the new world order.

Such shifts threaten to leave Obama’s earlier warning behind as a quaint reminder of older standards. For instance, exposing someone’s financial conflict of interest used to be a surefire way to destroy their credibility as a neutral, objective truthteller. But how do we adapt if that equation has changed? As Sarah Banet-Weiser has shown in Authentic, you can now sell out and be authentic, you can brand your authenticity. You can make your name as a mysterious, counter-cultural graffiti artist speaking truth to power, and then make a killing auctioning your piece at Sotheby’s, having the piece rip itself up on front of the buyer’s eyes – and they will love how real it is. In such times, can we really win the battle for reason by showing how transparent and independent our fact-checkers are?

Truth isn’t truth

Today, we often say truth is in crisis. The emblematic moment was the Marches for Science, which brought out outrage, but also a certain Sisyphean exasperation. Haven’t we been through this already? Surely truth is truth? Surely the correct path of history has already been established, and what must be done is to remind everyone of this?

Well, Rudy Giuliani has the answer for us: truth isn’t truth. Facts are in the eyes of the beholder, or at least, nowadays they are. Or, to be less glib: the struggle today is not simply between truth and ignorance, science and anger – a binary in which the right side goes without saying, and the wrong side is the dustbin of history screaming and wailing for the hopefully final time. Rather, it is a struggle over what kinds of authorities, what kinds of ways of talking and thinking, might count as rational, and how everybody’s trying to say the data and the technology are on their side.

It’s a twisted kind of Enlightenment, where the call to know for yourself, to use Reason, doesn’t unify us on common ground, but becomes a weapon to wield against the other side. Insisting on the restoration and revalorisation of objective journalism or faith in objective science might be tempting, and certainly an essential part of any realistic solution. But taken too far, they risk becoming just as atavistic as MAGA: a reference point cast deep enough into the mist, that it sustains us as fantasy precisely as something on the cusp of visibility and actuality. A nice dream about Making America Modern Again.

Information has always required an expansive set of emotional, imaginative, irrational investments in order to keep the engines running. What we see in self-tracking and charismatic entrepreneurs are emerging ‘disruptive’ groups that transform the ecosystem for the production and circulation of such imaginations. We might then ask: what is the notion of the good life quietly holding up, and spreading through, the futurism of smart machines or the paranoid reason of charismatic influencer?